Visual arts of the United States

Albert Bierstadt, The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Peak, 1863, Hudson River School

|

|||

|

|||

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, also known as The Athenaeum and The Unfinished Portrait, 1796, is his most celebrated and famous work.

|

Visual arts of the United States refers to the history of painting and visual art in the United States. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, artists primarily painted landscapes and portraits in a realistic style. A parallel development taking shape in rural America was the American craft movement, which began as a reaction to the industrial revolution. Developments in modern art in Europe came to America from exhibitions in New York City such as the Armory Show in 1913. Previously American Artists had based the majority of their work on Western Painting and European Arts. After World War II, New York replaced Paris as the center of the art world. Since then many American Movements have shaped Modern and Post Modern art. Art in the United States today covers a huge range of styles.

Contents |

Eighteenth century

After the Declaration of Independence in 1776, which marked the official beginning of the American national identity, the new nation needed a history, and part of that history would be expressed visually. Most of early American art (from the late 18th century through the early 19th century) consists of history painting and portraits. Painters such as Gilbert Stuart made portraits of the newly elected government officials, while John Singleton Copley was painting emblematic portraits for the increasingly prosperous merchant class, and painters such as John Trumbull were making large battle scenes of the Revolutionary War.

Nineteenth century

America's first well-known school of painting—the Hudson River School—appeared in 1820. As with music and literature, this development was delayed until artists perceived that the New World offered subjects unique to itself; in this case the westward expansion of settlement brought the transcendent beauty of frontier landscapes to painters' attention.

The Hudson River painters' directness and simplicity of vision influenced such later artists as Winslow Homer (1836–1910), who depicted rural America—the sea, the mountains, and the people who lived near them. Middle-class city life found its painter in Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), an uncompromising realist whose unflinching honesty undercut the genteel preference for romantic sentimentalism. Henry Ossawa Tanner who studied with Thomas Eakins was one of the first important African American painters.

Paintings of the Great West, particularly the act of conveying the sheer size of the land and the cultures of the native people living on it, were starting to emerge as well. Artists such as George Catlin broke from traditional styles of showing land, most often done to show how much a subject owned, to show the West and its people as honestly as possible.

Many painters who are considered American spent some time in Europe and met other European artists in Paris and London, such as Mary Cassatt and Whistler.

Twentieth century

Controversy soon became a way of life for American artists. In fact, much of American painting and sculpture since 1900 has been a series of revolts against tradition. "To hell with the artistic values," announced Robert Henri (1865–1929). He was the leader of what critics called the Ashcan school of painting, after the group's portrayals of the squalid aspects of city life. American realism became the new direction for American visual artists at the turn of the century. In photography the Photo-Secession movement led by Alfred Steiglitz made pathways for photography as an emerging art form. Soon the Ashcan school artists gave way to modernists arriving from Europe—the cubists and abstract painters promoted by the photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) at his 291 Gallery in New York City. John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Alfred Henry Maurer, Arthur Dove, Henrietta Shore, Stuart Davis, Stanton MacDonald-Wright, Morgan Russell, Patrick Henry Bruce, and Gerald Murphy were some important early American modernist painters.

After World War I many American artists also rejected the modern trends emanating from the Armory Show and European influences such as those from the School of Paris. Instead they chose to adopt academic realism in depicting American urban and rural scenes. Charles Sheeler, and Charles Demuth were referred to as Precisionists and the artists from the Ashcan school or American realism: notably George Bellows, Everett Shinn, George Benjamin Luks, William Glackens, and John Sloan and others developed socially conscious imagery in their works.

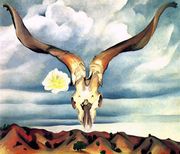

The American Southwest

Following the first World War, the completion of the Santa Fe Railroad enabled American settlers to travel across the west, as far as the California coast. New artists’ colonies started growing up around Santa Fe and Taos, the artists primary subject matter being the native people and landscapes of the Southwest. Images of the Southwest became a popular form of advertising, used most significantly by the Santa Fe Railroad to entice settlers to come west and enjoy the “unsullied landscapes.” Walter Ufer, Bert Greer Phillips, E. Irving Couse, William Henry Jackson, and Georgia O'Keeffe are some of the more prolific artists of the Southwest.

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was another significant development in American art. In the 1920s and 30s a new generation of educated and politically astute African-American men and women emerged who sponsored literary societies and art and industrial exhibitions to combat racist stereotypes. The movement showcases the range of talents within African-American communities. Though the movement included artists from across America, it was centered in Harlem, and work from Harlem graphic artist Aaron Douglas and photographer James VanDerZee became emblematic of the movement. Some of the artists include Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Charles Alston, Augusta Savage, Archibald Motley, Lois Mailou Jones, Palmer Hayden and Sargent Johnson.

New Deal Art

When the Great Depression hit, president Roosevelt’s New Deal created several public arts programs. The purpose of the programs was to give work to artists and decorate public buildings, usually with a national theme. The first of these projects, the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), was created after successful lobbying by the unemployed artists of the Artists' Union. The PWAP lasted less than one year, and produced nearly 15,000 works of art. It was followed by the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (FAP/WPA) in 1935, which funded some of the most well-known American artists. Several separate and related movements began and developed during the Great Depression including American scene painting, Regionalism, and Social Realism. Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood, Ben Shahn, Joseph Stella, Reginald Marsh, Isaac Soyer, Raphael Soyer, and Jack Levine were some of the best known artists.

Abstract Expressionism

In the years after World War II, a group of New York artists formed the first American movement to exert major influence internationally: abstract expressionism. This term, which had first been used in 1919 in Berlin, was used again in 1946 by Robert Coates in The New York Times, and was taken up by the two major art critics of that time, Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg. It has always been criticized as too large and paradoxical, yet the common definition implies the use of abstract art to express feelings, emotions, what is within the artist, and not what stands without.

The first generation of abstract expressionists was composed of artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, Phillip Guston, Ad Reinhardt, Hans Hofmann, James Brooks, Richard Pousette-Dart, William Baziotes, Mark Tobey, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Theodoros Stamos, Jack Tworkov and others. Though the numerous artists encompassed by this label had widely different styles, contemporary critics found several common points between them.

Many first generation abstract expressionists were influenced both by the Cubists' works (black & white copies in art reviews and the works themselves at the 291 Gallery or the Armory Show), and by the European Surrealists, most of them abandoned formal composition and representation of real objects; and by Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Often the abstract expressionists decided to try instinctual, intuitive, spontaneous arrangements of space, line, shape and color. Abstract Expressionism can be characterized by two major elements - the large size of the canvases used, (partially inspired by Mexican frescoes and the works they made for the WPA in the 1930s), and the strong and unusual use of brushstrokes and experimental paint application with a new understanding of process.

The emphasis and intensification of color and large open expanses of surface were two of the principles applied to the movement called Color field Painting. Ad Reinhardt, Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Barnett Newman were categorized as such. Another movement was called Action Painting, characterized by spontaneous reaction, powerful brushstrokes, dripped and splashed paint and the strong physical movements used in the production of a painting. Jackson Pollock is an example of an Action Painter: his creative process, incorporating thrown and dripped paint from a stick or poured directly from the can; he revolutionized painting methods. Willem de Kooning famously said about Pollock "he broke the ice for the rest of us." Ironically Pollock's large repetitious expanses of linear fields are also characteristic of Color Field painting as well, and art critic Michael Fried pointed that out in his essay for the catalog of Three American painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Frank Stella at the Fogg Art Museum in 1965. Despite the disagreements between art critics, Abstract Expressionism marks a turning-point in the history of American art: the 1940s and 1950s saw international attention shift from European -Parisian- art, to American -New York- art.

Color field painting went on as a movement: artists in the 1950s, such as Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, and in the 1960s, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland, and Helen Frankenthaler, sought to make paintings which would eliminate superfluous rhetoric with large, flat areas of color.

After Abstract Expressionism

During the 1950s abstract painting in America evolved into movements such as Neo-Dada, Post painterly abstraction, Op Art, hard-edge painting, Minimal art, Shaped canvas painting, Lyrical Abstraction, and the continuation of Abstract expressionism. As a response to the tendency toward abstraction imagery emerged through various new movements like Pop Art, the Bay Area Figurative Movement and later in the 1970s Neo-expressionism.

Lyrical Abstraction along with the Fluxus movement and Postminimalism (a term first coined by Robert Pincus-Witten in the pages of Artforum in 1969)[1] sought to expand the boundaries of abstract painting and Minimalism by focusing on process, new materials and new ways of expression. Postminimalism often incorporating industrial materials, raw materials, fabrications, found objects, installation, serial repetition, and often with references to Dada and Surrealism is best exemplified in the sculptures of Eva Hesse.[1] Lyrical Abstraction, Conceptual Art, Postminimalism, Earth Art, Video, Performance art, Installation art, along with the continuation of Fluxus, Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting, Hard-edge painting, Minimal Art, Op art, Pop Art, Photorealism and New Realism extended the boundaries of Contemporary Art in the mid-1960s through the 1970s.[2]

Lyrical Abstraction shares similarities with Color Field Painting and Abstract Expressionism especially in the freewheeling usage of paint - texture and surface. Direct drawing, calligraphic use of line, the effects of brushed, splattered, stained, squeegeed, poured, and splashed paint superficially resemble the effects seen in Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting. However the styles are markedly different.

During the 1960s and 1970s painters as powerful and influential as Adolph Gottlieb, Phillip Guston, Lee Krasner, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Richard Diebenkorn, Josef Albers, Elmer Bischoff, Agnes Martin, Al Held, Sam Francis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, Gene Davis, Frank Stella, Joan Mitchell, Friedel Dzubas, and younger artists like Brice Marden, Robert Mangold, Sam Gilliam, Sean Scully, Elizabeth Murray, Walter Darby Bannard, Larry Zox, Ronnie Landfield, Ronald Davis, Dan Christensen, Susan Rothenberg, Ross Bleckner, Richard Tuttle, Julian Schnabel, and dozens of others produced vital and influential paintings.

Other Modern American Movements

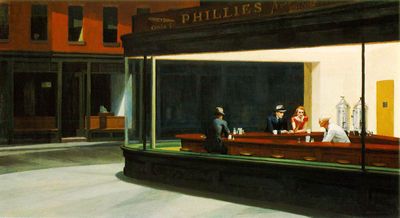

Members of the next artistic generation favored a different form of abstraction: works of mixed media. Among them were Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) and Jasper Johns (1930- ), who used photos, newsprint, and discarded objects in their compositions. Pop artists, such as Andy Warhol (1930–1987), Larry Rivers (1923–2002), and Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), reproduced, with satiric care, everyday objects and images of American popular culture—Coca-Cola bottles, soup cans, comic strips. Realism has also been popular in the United States, despite modernist tendencies, such as the city scenes by Edward Hopper and the illustrations of Norman Rockwell. In certain places, for example Chicago, Abstract Expressionism never caught on; in Chicago, the dominant art style was grotesque, symbolic realism, as exemplified by the Chicago Imagists Cosmo Campoli (1923–1997), Jim Nutt (1938- ), Ed Paschke (1939–2004), and Nancy Spero (1926–2009).

Notable figures

A few American artists of note include: Ansel Adams, John James Audubon, Thomas Hart Benton, Albert Bierstadt, Alexander Calder, Mary Cassatt, Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Cole, Edward S. Curtis, Richard Diebenkorn, Thomas Eakins, Jules Feiffer, Helen Frankenthaler, Arshile Gorky, Marsden Hartley, Al Hirschfeld, Hans Hofmann, Winslow Homer, Georgia O'Keeffe, Lee Krasner, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Dorothea Lange, Roy Lichtenstein, Morris Louis, John Marin, Agnes Martin, Jackson Pollock, Man Ray, Robert Rauschenberg, Frederic Remington, Manuel Rivera-Ortiz, Norman Rockwell, Mark Rothko, Albert Pinkham Ryder, Cindy Sherman, David Smith, Frank Stella, Gilbert Stuart, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Andy Warhol, Frank Lloyd Wright, Andrew Wyeth, N.C. Wyeth

See also

- Abstract Expressionism

- Aesthetics

- American Impressionism

- American modernism

- American realism

- American scene painting

- Art education in the United States

- Colorfield painting

- History of painting

- Late Modernism

- List of American artists

- Lyrical Abstraction

- Modernism

- Native American art

- Regionalism

- Sculpture of the United States

- Social Realism

- Synchromism

- Visual arts of Chicago

- Western painting

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Movers and Shakers, New York, "Leaving C&M", by Sarah Douglas, Art+Auction, March 2007, V.XXXNo7.

- ↑ Martin, Ann Ray, and Howard Junker. The New Art: It's Way, Way Out, Newsweek July 29, 1968: pp.3,55-63.

Sources

Pohl, Frances K. Framing America. A Social History of American Art. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002 (pages 74–84, 118-122, 366-365, 385, 343-344, 350-351 )

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||